Culture, Art and Discernment

by Mother Macaria

If you don’t know the kind of person I am

and I don’t know the kind of person you are

a pattern that others made may prevail in the world

and following the wrong god home we may miss our star.

For there is many a small betrayal in the mind,

a shrug that lets the fragile sequence break

sending with shouts the horrible errors of childhood

storming out to play through the broken dyke.

And as elephants parade holding each elephant’s tail,

but if one wanders the circus won’t find the park,

I call it cruel and maybe the root of all cruelty

to know what occurs but not recognize the fact.

And so I appeal to a voice, to something shadowy,

a remote important region in all who talk:

though we could fool each other, we should consider —

lest the parade of our mutual life get lost in the dark.

For it is important that awake people be awake,

or a breaking line may discourage them back to sleep;

the signals we give — yes or no, or maybe —

should be clear: the darkness around us is deep.

A Ritual to Read to Each Other

By William Stafford

****

If you don’t know the kind of person I am

and I don’t know the kind of person you are

a pattern that others made may prevail in the world

and following the wrong god home we may miss our star.

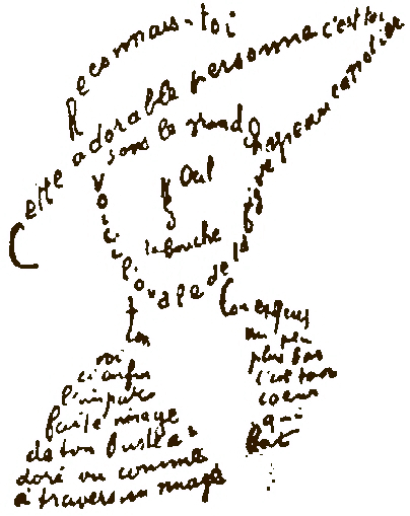

The Orthodox spiritual life requires that we learn to understand ourselves and our passions and temptations, yet we live in a cultural morass of unconscious and deceptive influences expressed through culture and inasmuch as we expose ourselves to these things passively, without examination, we expose ourselves to forces that undermine our faith and our souls just as surely as the knight in John Keat’s poem, La Belle Dame sans Merci rode into danger, unable to identify his enemy. We need to learn to examine these elements of culture carefully, to discern what is behind them and to understand what parts of them are useful and what are harmful. I am not familiar enough with movies or media or contemporary music to discuss what is out there, so for this essay I am using what I know—poetry and literature This may serve as a lens for the broader labor of discernment we need to undertake for our salvation lest, as poet William Stafford wrote, we miss our star.

One cannot even write a haiku without expressing a worldview. In fact, if it is a true haiku it will have somewhat of a Buddhist worldview. As for instance Basho’s classic:

In an Ancient pond

a frog leaps

Kersplash!

To the Japanese mind this is a very Zen sort of poem—you have quiet/perfection/absorption. This stasis is intersected by change and then its effects. There are reams of philosophical works written on this little three-line poem, but the point is that this is not just a descriptive poem and it is not about a frog. It is not just a series of words arranged to arrive at the assumed 5-7-5 syllable count, though these are elements that tell you about the poet’s intent. Not every work of art is going to have the deliberate philosophical underpinning that Basho’s haiku does—but it will reflect the way the artist sees the world in some way. This is part of what makes it interesting. What is potentially dangerous is approaching it blindly, as something to be consumed, without reflection as the knight in Keats’s poem approached the beautiful lady without mercy—as it turns out, a rather accurate description of a demonic encounter under the guise of romantic love. If you continually read works with a rebellious or anti-traditional spirit in an unreflective way, then next thing you know you will be disrespecting your priest or your bishop or finding reasons why you don’t really need to fast. It can be a subtle change — as William Stafford says: “a small betrayal in the mind/ that makes the fragile sequences break.”

I am not advocating that one needs to avoid anything that might not be Orthodox. In our world that isn’t even possible. In 19th century Russia a spiritual father could say don’t read novels. It was an Orthodox culture and the predominant worldview could keep you out of trouble. Today you would be considered some kind of fanatic if you kept your child from reading novels — and that would never be enough — when there are movies and music and every other form of art and media trying to pollute his soul. We need to reflect carefully and thoughtfully about what we choose to read or view. Often a work that is entertaining has a very deliberate agenda to it. Story telling is a way to examine ideas and some of our best Orthodox writers have been masters of that craft—for instance Dostoyevsky and Papadiamantis. But literature is about something more than ideas too — it is about having an inner world and an inner life. It provides ways and angles for reflecting on our lives, thoughts and relationships. It can be about having a real inner world or instead something designed to replace that real, spiritual inner world — with a fantasy. This is also a danger.

And as elephants parade holding each elephant’s tail,

but if one wanders the circus won’t find the park,

I am not talking about fantasy as a genre but about living a fantasy. As a literary genre, fantasy is ancient. Shakespeare, Chaucer and Spencer used fantasy. Most of our folk tales are based on fantasy but these things often express metaphors and lessons about life. Even the most recent works of speculative fiction only manage to write about human nature and how we behave or understand ourselves. Sometimes these works are elaborate parables for a particular philosophy. Living a fantasy is another problem.

Years ago, I was told that Fr. Seraphim Rose was against fairy tales, so I needed to understand what this was about since Fr. Seraphim was an important Orthodox thinker. I began to research all of his writings for this idea and I discovered that although Fr. Seraphim used the phrase “fairy tale” quite often and in a pejorative way, he was always talking about our American world view not fairy tales. He had another word for it as well: “Disneyland”. In our culture we like to subscribe to the somewhat magical New Age idea that we can create our own reality. Sooner or later, by God’s merciful providence, this kind of thing will come crashing down around the ears. There are some rather enjoyable fairy tales about it — like the one about the fisherman who was granted wishes by a fish. The fisherman’s wife wanted to be the pope and that didn’t work out well. Many projects and ideas in American culture are like this—built on sand. I don’t think I need to provide examples of this.

So, the reading of fantasy literature is one thing and can be useful or harmful but living in a world of your own creation without attention to your Creator and the way He created the cosmos is a serious problem. When something strikes you, whether as beautiful or as revolting, our Orthodox spiritual writings teach us that we should examine this and understand why. Does this idea appeal to me because of my passions or hidden sins? Do I reject that idea too quickly or for the wrong reasons? One needs to attend to what is being said as much as to the beautiful or apt words and images. This is true of every form of literature or art. Children’s books are full of agendas for what the author wants the child to think. Authors use fantasy to teach children how to think because this is close to what the child does when he is daydreaming or playing. Adult literature does the same thing. The ideas behind a work may be clumsy and obvious or they may be so much a part of the polluted air we breathe that we can’t see it. A captivating story is a more effective presentation of an idea than a good argument. Let us take a look at two very popular children’s works, The Harry Potter Series and The Wizard of Oz.

I call it cruel and maybe the root of all cruelty

to know what occurs but not recognize the fact.

The Harry Potter books have been quite controversial. Some insist that they are utterly dangerous and demonic and there are some who point out Christian themes and the battle between good and evil in them. The debate is typically polarized as so many things are in the world — as if poised to prevent serious thought. No one addresses the actual problems — like the fact, for instance, that if your child goes to a public school he or she will be exposed to these works. If you forbid them, can you guarantee that you will be obeyed? Some children will reject them — not many. And why forbid them unless you are equally careful about every other thing your child reads. There are far worse books than Harry Potter. And many of them are written for children. For example, there is a series called His Dark Materials by Phillip Pulman, in which the author tries to destroy the Christian world view and kill the Ancient of Days, as he understands it. If you do read this series, read all of it. The books get darker and more anti-Christian with each volume — perhaps because a parent is unlikely to read more than the first one. What is really needed with the Harry Potter is for the parent to help the child learn to think about the stories. What is magic, as the author expresses it? Is this what it is in the real world? What are the dangers? There are so many saints lives that could be drawn in as examples of the actual dangers. And this process would pull the child’s mind away from the fast-paced adventures that make the expressed ideas of the story sink in unnoticed and it will help him learn to think about what is truly Christian and what is not — a lesson that will be applied to other works.

I choose The Wizard of Oz because it is considered a classic. We all grew up with it. It is practically a cultural heresy to criticize the work. But if you start examining the book and its author you will find the same issues present that are found in the Harry Potter books. The author, Frank Baum was a spiritualist who dabbled quite a bit in the occult. I remember how surprised I was as a child to hear for the first time in the Wizard of Oz that there was such a thing as a “good witch.” Truly, Glenda Goodwitch seems like a very positive character who helps Dorothy get home eventually, though she fails to mention that Dorothy could have gone home easily anytime without having to face so many dangers. There is a questionable quality to this kind of good—very much like the Irish fairy tales where the fairies are always deceptive but are called “good” because it is dangerous to offend them. But more than that, the idea that there is a “good” or white witchcraft that is safe has become endemic in our culture. None of the children I went to school with had mothers who practiced witchcraft. That can no longer be said of children in public schools today. And this shows how easily a suggestion made to children can become a cultural meme. If you will reject Harry Potter then you need to reject Wizard of Oz. Surely it would be better though to engage children in a dialogue as they read such stories. Is this asking too much? Phllip Pullman doesn’t think it too much to engage them in polemics about their faith. You could ask, “Is there such a thing as a good witch?” Then explain what a witch is. After all, they definitely will not learn this in school. I remember my mother removing a Ouija board from a pile of games we received one Christmas—there was no explanation, so I was curious. I would have been better served, even at a young age, to know why. I did not learn why she had removed it until I was a college and there was a Ouija board present. You could explain that there are people who don’t know any better, who don’t understand that they are serving the devil. Often, they don’t. You would say the same kind of thing about the dementors in the Harry Potter series —they are just fantasies — but there are demons who behave this way and dementors came out of the author’s experience with depression.

Aside from the obvious link between magic and the demonic there is an interesting connection between magic and technology. J.R. R. Tolkien. pointed out the similarities between magic and the machine in some of his letters. He wrote that both

…will lead to the desire for Power, for making the will more quickly effective—and so to the Machine (or Magic). By the last I intend all use of external plans or devices (apparatus) instead of development of the inherent inner powers or talents—or even the use of these talents with the corrupted motive of dominating: bulldozing the real world or coercing other wills. The Machine is our more obvious modern form though more closely related to Magic than is usually recognized. (The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien Selected and Edited by Humphrey Carpenter with the assistance of Christopher Tolkien)

Both magic and technology tend to corrupt the will. They create a dissatisfaction with the world as we know it so that this world can seems less bright, absent of wonder or interest. After imagining what can be done instantly, simple, menial tasks can be emptied of any satisfaction—work becomes drudgery and skills and crafts that require labor and diligence lose their savor. So, we may be caught in a kind of afterglow or glamor of some new work, such as a Star Wars movie, but it is always worth considering what has it added to the soul?

And so I appeal to a voice, to something shadowy,

a remote important region in all who talk:

though we could fool each other, we should consider —

lest the parade of our mutual life get lost in the dark.

If we want to make an active and conscious labor to understand how we are affected by the world around us, then we have to actively practice and understand our Orthodox faith, or we waste our time. In addition to the fasts and sacraments of the Church one needs to read spiritual books so that lives and writings of the saints and elders become a mirror or measuring stick to overcome the distortions of this age. This is the labor of a lifetime. If one is actively reading good books about the spiritual life, then one is less likely to be attracted to works that inflame the passions or that are deceptively evil. Even so, one has to be aware of the harmful effects of a work that inflames the passions or is based on occult or harmful ideas or involves looking at something evil. Even an apparently good work can move one to passions that should be examined. What is going on when a book stirs feelings of revenge in you against one of its characters? It may not be a sin, but it is a tendency toward sin that needs watchfulness. Evil though, is hypnotic. As Dante Gabriel Rosseti wrote in his Aspecta Medusa:

Andromeda, by Perseus saved and wed,

Hankered each day to see the Gorgon’s head:

Till o’er a fount he held it, bade her lean,

And mirrored in the wave was safely seen that death she lived by.

Let not thine eyes know

Any forbidden thing itself, although

It once should save as well as kill; but be

Its shadow upon life enough for thee.

It is harmful to the eye of the soul to contemplate evil. So, whether it is something occult or simply a crime novel one has to be careful. I know someone who had to give up murder mysteries because she always got depressed afterwards. The link was there but not obvious.

Finally, something should be said about the imagination. The writers of the Philokalia tell us repeatedly not to use imagination in prayer It is not a warning to never use the imagination — you can’t design a house without the imagination, much less build one. This warning is very similar to the Old Testament commandment to not build graven images. God is beyond any image we can produce from our imaginations. If you put an image of your own creation in place of God, then you worship something false instead of the true God and your imagination can be influenced by evil. So, this is at least partially about not mistaking the products of your mind for God—otherwise you cannot give Him the worship that is His due. It is also about learning not to worship what you create —such a human tendency. Thus, the writings on spiritual life are about prayer, not about art and culture. Though, one would obviously not want to imbibe of an art form if one could not do it prayerfully.

For it is important that awake people be awake,

or a breaking line may discourage them back to sleep;

Orthodox spiritual practice is essential as well as the humility to trust the spiritual wisdom entrusted to us. It is important to avoid accepting your entertainment passively because you are unwinding or want to escape the overwhelming pressures of the world. Having a spiritual life requires vigilance. It is important to identify what is behind whatever form of art or media you are partaking of. What is the author’s motivation? What are the dominating thoughts, suggestions, passions of the work and how is the persuasion of the piece effective? Truly it would be good to develop an Orthodox school of literary criticism. That is a discipline that is little understood or appreciated but it can be quite insightful. Any good essay written about a literary work can be insightful and not all of it is written by and for English professors. I have found wonderful cultural insights in essays by Wendell Berry, for instance or Czeslaw Milosz. There is a new book out with some very good literary essays by Orthodox writer, Donald Sheehan called The Grace of Incorruption. We can cobble together works that are compatible with our understanding of the world and we can find works that are Orthodox as well to help us understand the strange new world we find ourselves living in. As William Stafford wrote:

the signals we give — yes or no, or maybe —

should be clear: the darkness around us is deep.

Originally published in The Diocesan Observer #1359 –April, May June 2018

Used by permission of the author.

Please send comments on or submissions to our blog to annetteglass03@gmail.com